Deadwood as Milch’s attempt at a purely American creation myth

¶ by Rob Friesel Work with me here: When David Milch hallucinated the opening scene to what would become Deadwood, when he gathered up his personal assistant(s) into a darkened room and reclined on the couch to spill forth from his amygdala exactly what he was seeing beyond his third eye, he was leaking his fever-dream vision of a purely American creation myth.

Work with me here: When David Milch hallucinated the opening scene to what would become Deadwood, when he gathered up his personal assistant(s) into a darkened room and reclined on the couch to spill forth from his amygdala exactly what he was seeing beyond his third eye, he was leaking his fever-dream vision of a purely American creation myth.

I’m convinced of this.

Listen: Milch saw a gap. Every culture worldwide, living or dead, has a ripe and complex history, rich with detailed mythology and folklore. And though many of these cultures’ mythologies are suppressed under some latter-day predominant macro-culture 1, the fact of the matter is that each of these mythologies feature some kind of creation myth 2. What Milch saw, was that America – melting pot or not – has emerged as a pretty interesting cultural entity, one that is likely to have a long-lasting legacy. But where was its creation myth? Was it to succumb to the fate of borrowing the creation myths of its patchwork constituents? Was it to delegate its mythology to the cultures native but otherwise systematically destroyed 3? Or was it to move softly into its own future without regard for this dare-we-say necessity?

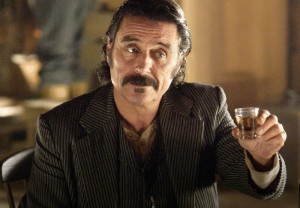

So Milch let his Jungian subconscious run wild on whiskey and opium, digging deep and coming up with Deadwood.

It seems an unlikely candidate for a creation myth: set against the backdrop of the last gold rush in the continental United States 4, we find a story arc filled with frequent fatal violence and destruction, where the men are many and the women are few – and when we do have women, they’re mostly whores, save for the alcoholic tom-boy and the widows 5 – so we’re not exactly basking in proxies for Gaia here.

Where then am I coming up with this absurd theory?

Looking at any creation myth, what are you really looking at? Each is a story rendering somethingness out of nothingness, order out of chaos.

And in light of that sentiment, what then is Deadwood except a creation myth that rejects the notion of Genesis and a set beginning? An illegal camp at the end of time 6 come together to prospect for gold – what cup runneth over with chaos more than that one? But even as we enter this scene, we are leaving it. We 7 enter the camp of Deadwood through the eyes of Seth Bullock 8, who looks to bring one type of order with him (in the form of a hardware store) and in so doing has the task thrust upon him of bringing another type of order (i.e., “you’re the sheriff now”). The narrative path put down for us from the very beginning is exactly this: ordo ab chao.

What then makes it a “purely American” creation myth? If we consider that America (in the sense of “that composite of peoples and geographic territories that became (and/or became again) a part of the United States of same”) is a distinct and unique culture in the world, we can trace it back to some distinct beginning that comes “in the middle” of the lives of every other pre-existing culture worldwide. A nascent “America” is already quite aware of who it is 9 and what it’s capable of; America is already aware of its beginnings and the growth it will need (or at least want) to do; America starts with a past dismissed as someone else’s and a future borrowed from its coming constituents.

Listening closely to Milch’s Deadwood, we hear the echoes of that. Characters speak seldom of the camp’s past; the past is something that happened “somewhere else” – Chicago, Montana, away on the Missi’sip’. And when characters speak of the future, though they yearn for positive outcomes, their fates are so often bound-up in capricious forces from without: political interests from beyond the hills, large-scale mining operations, clandestine investigators of every color and stripe; but also every color and stripe of new venture and family.

And in that regard we have a bit of cheeky play on Milch’s part with respect to family and America’s long pattern of growth through amalgamation and a further stab at rejecting the notion of Genesis in his “purely American” creation myth. Milch’s Deadwood grows but does not give birth. If we consider that a common trope in creation myths is one of “The Great Mother”, Milch’s does away with this all together. His milieu, while not devoid of feminine characters, is peppered with minor, background women – whores, mostly – and a few moderate-to-major players in the narrative arc. And of those moderate-to-major players, we have two whores 10, a rough-riding alcoholic tom-boy (that scouted for General Custer and rode with Wild Bill Hickock), and two widows. Milch practically shoves aside pregnancy (there are a few off-hand mentions and “the one that matters” ends before it shows 11) and does away with any treatments of childbirth all together. What’s left of motherhood is Milch bending it to his vision of his purely American creation myth: the first mother we encounter is slain by road agents; the child of the slain mother is cared for first by a doctor (male) and then by the alcoholic tom-boy (barely female?) before coming finally to rest as the ward of the then-still-addicted-to-laudanum widow (and though woman, she is barely more mature, emotionally speaking, than the child under her care) who requires additional assistance (first from a whore and then from the tutor/double-agent) for quite a while 12; Seth Bullock’s son is actually his nephew and is only adopted as such through a marriage of obligation (and that son/nephew perishes not long after arriving in the camp); other children are seen to leave camp; the one pregnancy we’re given to consider as serious does not last.

All of this points to Milch telling us that there is growth, but that it comes with costs and more often we will discover it stems from some amalgamation of existing bodies and not via “new births”, as it were. The story is a complex apparatus 13 that works well as a creation myth 14 in the American historical and cultural contexts. The abrupt (arguably disappointingly so) ending even fits the picture of a creation myth; what else is a creation myth but a way of setting the stage and constructing the context for the myths that come afterward 15?

- Judeo-Christian traditions, I’m looking in your direction.[↩]

- Judeo-Christian tradition: I know you’ve got yours too, but it’s pretty weaksauce when compared to some.[↩]

- A tip of the ironic hat there?[↩]

- Which incidentally, we could also remark coincides with America’s Centennial year.[↩]

- One a recovering opium addict struggling with her own motherly identity (though scarcely more than a child herself) and the other re-married and a bit cold (certainly at first, and anyway she’s a bit late to arrive on the scene); but more on that later.[↩]

- Try thinking of 1876, America’s Centennial year as a convenient way of marking (at the very least) a benchmark or end of an era. It’s then additionally convenient that we have a narrative arc working under the auspices of the continental United States’ last gold rush (speaking of endings to eras).[↩]

- ”The Viewers”, of course.[↩]

- And let us please not get started about how laden with mythological import (and double-meanings) “Seth” is. If anything, history made this supremely easy on Milch.[↩]

- Laughable, academic arguments re identity aside, thank you.[↩]

- Well, one whore and one madam-née-whore.[↩]

- And were this essay significantly longer (say: book-length?) then I would wager this worthy of a chapter to itself.[↩]

- And that’s not even diving into the complex interplay of Sophia vs.Swearengen re how he would have her destroyed only to relent. Consider how fraught that conflict is w/r/t/ our overall ordo ab chao narrative arc.[↩]

- I feel like I’m just barely scratching the surface in this space here.[↩]

- Though it is based loosely on factual historical events. But that’s certainly an aside.[↩]

- Too bad nothing comes afterward?[↩]

Leave a Reply