documenting my homebrewing technique

¶ by Rob FrieselTo bastardize the Rifleman’s Creed: This my brewing technique. There are many like it, but this one is mine. Indeed there are many articles about technique and process — everything from “basics for beginners” to super-specific niche techniques. I do not pretend to be an expert, but I also thought that a post like this could serve two useful purposes. First, capturing my technique it would help me to clarify what I’m doing and why. Second, if there is someone else out there looking to follow a similar process, perhaps it can help guide them.

So, the short-short summary version: I typically brew 5 gallon all-grain brew-in-a-bag (BIAB) batches of my own design, and package with a mix of kegging and bottling. Occasionally I’ll mix it up with an extract or partial mash batch, or a 6 gallon batch split two ways, or a 3 gallon experimental batch; but I haven’t brewed from a kit since August 2015.

Contents:

- Assumptions, Constants, and Definitions

- Beer Design

- Yeast and Starters

- Brew Day

- Fermentation

- Dry Hopping and Flavor Additions

- Packaging

- Cleaning

- Parting Thoughts

Assumptions, Constants, and Definitions

A couple of quick notes to level-set before going into the details of my process.

- Everything is cleaned as soon as possible. At a minimum things get rinsed and wiped down with a soft cloth. Kettles, carboys, and kegs will get a 25 minute soak in PBW before being scrubbed out.

- Everything gets sanitized. Anything that is going to touch wort or beer will have been sanitized with at least 60 seconds of contact time with Star San. I prepare a Star San solution of 1 oz. per 5 gallons; I fill up a spray bottle with that and keep the rest in a lidded food-safe bucket. Note that I won’t call out anywhere else in this document where I perform the sanitizing step or else the phrase “make sure to sanitize it first” will appear about a hundred times.

- Seattle water with some tinkering. From 2017-2019, my water source was the Champlain Water District; in summer 2019, we moved to Seattle, and now I use that water. I run it through a carbon filter to reduce any extant chlorine; afterward, I add brewing salts (e.g., calcium chloride, calcium sulfate, etc.) to achieve the desired profile that comes out of the “Water” tab in BeerSmith 3.

- Brew house efficiency is assumed as 70%. After nearly 100 batches, I’ve settled on 70% as my planned brew house efficiency for moderate-gravity batches. I use 65% for high-gravity batches. (Rationale posted here.)

- BIAB. Brew-in-a-bag.

- DME. Dry malt extract.

- LME. Liquid malt extract.

Beer Design

I started designing my own beer formulations in March 2015, just seven months after my first extract kit. The first beer that I brewed of my own design was a Kölsch-like; with one exception (my first IPA), they have all been “of my own design” since then.

Once I get an inspiration for an idea, my design process is generally to do an initial sketch, compare my formulation with similar recipes and the style guidelines, then to enter it into BeerSmith to “do the math”.

Brewing Notes

I keep two brewing notebooks: one is a physical three-ring binder (vide supra) with scribbled-on brew day sheets and photocopies of recipes; the other (far more detailed one) is in Evernote.

In Evernote, I keep a running log of ideas: notes from conversations, links to articles, tasting notes from beers I’ve tried, etc. Once one of those ideas takes shape as something that I want to brew, it gets promoted to its own note.

When I start the “sketch” of the beer, I have a specific flavor profile in mind — an overall impression that I want to convey. Sitting down to do that sketch, I follow what I call the Strong Method, which is a beer design scheme adapted from Gordon Strong’s 2011 book, Brewing Better Beer. Strong writes: “Let the flavor profile drive the ingredients” — and then provides the following order in which to consider the ingredients:

- Yeast. Start with the strain. What are its attenuation and flocculation characteristics? What flavors does the strain contribute? What sorts of temperatures must I consider for fermentation?

- Grains and fermentables. What are the base grains? What flavors will these impart? Aromas? Do you need to use special techniques to get them to convert? Or to develop specific flavors? Colors? What will the mash schedule look like? How does that affect fermentability and body? After base grains, think about the character grains — crystal, roasted, and other specialty grains. Go through those questions again. If I’m using dark grain, consider steeping them instead of adding them to the main mash. Lastly, what other fermentables do I need? LME and/or DME? Honey? Other sugar adjuncts?

- Hops. Consider the bittering hops first. For the initial bittering charge, I like to use a single “clean” high-alpha variety; Galena is my go-to, but I’ll use Columbus if I want to accentuate an American character, or else Magnum for something more European. (2019-2020 has seen a lot of Warrior used in this way.) Then consider flavor/aroma hops; these are the late additions — i.e., in the last 5 minutes, or at knock-out, or in the whirlpool. This also includes any dry hops. There is a lot of flexibility in the flavor/aroma hop area. The sky is the limit, but I try not to use more than four varieties (Strong’s advice again); I generally do not use more than 2-3.

- Flavor agents. Optional. This is where I consider what other ingredients to work into the formulation. If I’ve got an idea that’s going to involve spices or fruit or something like that, this is where it comes into the mix. Does it go into the boil? Into the fermentor? At packaging?

- Water modification. Get into the BeerSmith 3 Water tab and set a profile based on the color and body of the beer. Carbon filter the tap water; add the specified grams of gypsum, calcium chloride, Epsom salt, table salt, and/or baking soda. Apply 88% lactic acid to get the pH just right.

Once I’ve got a first pass at the sketch, I ask myself What can I take away? Looking over my notes from Randy Mosher’s 2004 Radical Brewing, I summarized Chapter 7 (“Basic Drinkers”) with the phrase even simple can be special. I try to apply that rubric here.

With the sketch written down, I’ll compare it against style profiles and formulations for similar beers. If I’m making something “to style” (e.g., because I want to enter it into competition), then I compare it against what’s in the BJCP style guide. The style profile articles from BYO magazine and Josh Weikert’s “Make Your Best” series from Craft Beer & Brewing are great sources of information. I also compare against recipes that I see in books like Modern Homebrew Recipes (Strong, 2015) or Home Brew Beer (Hughes, 2013) or one of the other books on my shelf. These comparisons help me to further refine my idea.

Once I’ve taken two or three passes at the beer’s formulation, I’ll fire up BeerSmith and start entering in the ingredients. It’s a great tool for doing the math on quantities to get to the gravities and volumes I want.

Embrace Constraints

Rather than wish for limitless everything, I happily embrace the constraints I have. I’ve added equipment to my set up slowly and deliberately — only on an as-needed basis. By and large, I restrict my shopping to local homebrew supply stores. This helps to eliminate “choice paralysis”. For the most part I can get what I need this way, but if I absolutely must have some specific ingredient, I know I can order from online.

Yeast and Starters

I use a mix of liquid and dry yeast. Dry yeast is convenient, and I’ve found a couple of strains I like; I tend to get better results when I rehydrate. I mostly use liquid strains though, and I almost always make a starter.

Method for Starters

I use the “Starter” tool in BeerSmith to calculate the starter size. Two to three days before brew day, I fill my Erlenmeyer flask with the specified amount of water; I’ll weigh out an amount of light DME 1 to make a 1.038 wort (10 g DME per 100 mL of water) and add it. The flask goes directly on the stove and boils for 15 minutes. A drop or two of Fermcap is enough to prevent boil-overs but I watch it just the same. After boiling, I put it into an ice bath; this takes about 15 minutes to come down to temperatures suitable for pitching a starter. Once I pitch the yeast, the flask goes onto the stir plate.

The yeast spins on the stir plate for 24-48 hours to build up the cell count. On brew day, I will pitch the starter straight from the stir plate once the wort has been chilled to pitching temperature. (Always remember to remove the stir bar first!)

I used to cold crash the starter the night before brew day so that I could decant the supernatant. I have stopped doing this for two reasons. First, the Brülosophy experiment on this subject says it doesn’t make a statistically significant difference in taster perceptions. And secondly, a cold crash seems to defeat the purpose of the starter in the first place — i.e., what good is having a big colony of yeast if you just shocked them all into a semi-dormant state by throwing them in the refrigerator? If I want to decant, the yeast will flocculate well enough just by turning off the stir plate the night before brew day.

Rehydrating

To rehydrate dry yeast, I follow the recommended temperatures, water quantities, and times printed on the sachet. If no such recommendations are indicated, then I use the method detailed on the American Homebrewers Association website:

- Allow yeast sachet to warm to room temperature.

- Sanitize a small container.

- Obtain 10 milliliters water per 1 gram of yeast; heat it to between 95-105ºF.

- Sprinkle yeast on top of the water and cover with foil. Wait 15 minutes.

- Stir to form a cream and wait 5 more minutes.

- Pitch the yeast as soon as possible after that.

Yeast Harvesting

I have two methods for harvesting yeast. The first (and easiest) is to “over-build” a starter. For these instances, I follow the method described above but with two changes. First, after calculating the starter size in BeerSmith, I double it. Second, right before I go to pitch the yeast, I dump half of the slurry into a sanitized Mason jar.

However, if I did not over-build the starter, I follow this process:

- Boil a couple of Mason jars (quart jar + 2 × pint jars) in water for 15 minutes.

- Remove the jars from the pot, keeping as much water in them as possible. Place lids on the jars and allow them to cool for at least an hour.

- Add the water from the quart jar to the carboy and swirled it around to break up the sediment and put the yeast into suspension; let that settle for an hour.

- Pour from the carboy into the quart jar and place that into the refrigerator with the lid on. Let that settle for a couple of hours.

- Decant from the quart jar into the two pint jars. Put a piece of painter’s tape on the lid, labeling each with the strain, the generation, and the date they were harvested. Now they live in the refrigerator until they’re ready to be used.

When re-pitching from one of these jars, I’ll generally use the Mr. Malty calculator to give me a sense of the viability of the culture. If the viability is good (>70%) then I’ll just pitch it straight — decant the supernatant and pitch the slurry. If it’s “too old” then I’ll use a vitality starter on brew day and pitch.

In a nutshell, the vitality starter is 1 L of 1.038 wort but the yeast is spun on the stir plate for only four hours. The goal is to get sufficient oxygen into the yeast colony without necessarily allowing fermentation to start; with the yeast “activated” in this way, they can be pitched.

Brew Day

Brew day! For many homebrewers, other than the drinking part, this is what we live for. Brewing is certainly my happy place. For my part, brew day takes roughly this shape: heating the strike water, mashing, post-mash science, boiling the wort, chilling the wort, post-boil science, transferring to the carboy, more wort science, pitching, and (sighs) cleaning. All this takes about about 6 hours start to finish.

Mashing

As a BIAB brewer, I use a single vessel for mashing and boiling. I have a 10 gallon stainless steel Spike kettle. The kettle itself is lined with a brew bag from The Brew Bag.

BeerSmith provides the guidance on mash volumes and typically recommends approximately 2 qt./lb. I fill up the kettle and apply heat, checking every few minutes until it reaches about 6-8ºF above the mash temperature; then I place the grain bag into the kettle, fold the edges of the bag over the lip, and secure it with binder clips. I pour the grains in a little bit at a time, stirring to break up dough balls. I take the temperature of the mash. If it’s too high (e.g., >1-2ºF from the target mash temperature) then I let it stand with the lid off; I re-take the temperature every 2 minutes until it is where it needs to be. Once the temperature is correct, I wrap the kettle in insulating “battle armor” that I cut from a roll of Reflectix. 2

For the most part, I try to leave the mash alone. I check it after 10-15 minutes to take a pH reading and to record the temperature. If pH is too high, I will adjust it with 88% lactic acid. I typically take temperature readings every 15-30 minutes until the saccharification rest is complete.

If the temperature gets “too low” then I will remove the insulation and apply direct heat, checking the temperature every minute until it’s in the correct range again. That being said, “too low” is a judgment call and I don’t have a good rubric for that. As a side note: β-amylase is active between 131-150ºF and its “ideal” range is 142-146ºF. For that reason, most of my mashes start at approximately 150ºF and I just let them fall as much as they want.

For mash-out, I typically reserve 2-3 gallons of strike water from the main mash and boil that on the side. When the saccharification rest completes, I pour in the boiling water to raise the temperature to about 168ºF and hold it there for 10-15 minutes.

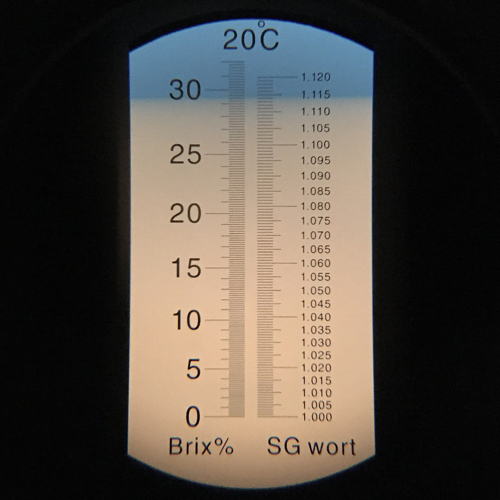

After the mash completes, I do a little science. I look at volume markers on my kettle to see how much wort I have. I take a couple drops of wort and place it on the prism of my refractometer. I write all those numbers down on the brew sheet (which will get summarized in the Evernote formulation sheet) and also enter it into BeerSmith.

As an aside, since most of the mashing is waiting, it’s a good time to do a little mise en place for the rest of the brew day.

Lautering

Not to over-simplify but being a single-vessel BIAB brewer, lautering is as simple as: “remove bag from wort and let drip; squeeze as desired.”

With BIAB, your brewing profiles are almost all “sparge optional”. For example, the built-in BeerSmith BIAB mash profiles assume that (1) the brewer is doing a full-volume mash/boil, and (2) that the BIAB mash is no-sparge.

One thing that I do every time is to squeeze the bag like crazy. When the mash is finished and I remove the grain bag from the kettle, place a grill grate on top of the kettle, and set the bag onto the grill to let it finish dripping. After the bag has finished dripping, I proceed to squeeze the bag to get all the sugar-laden wort out. When the squeezing is yielding little more than a trickle, that’s when I stop.

I already have some volume and gravity readings from when the mash completed, but I take those numbers again after the squeezing.

If my kettle volume is significantly lower than what I need, then I do what I refer to as a faux sparge. For a faux sparge, I determine how much water I need to top off the kettle to the target volume. I fill a pitcher with that much water. Then I slowly and gently pour that water over the grain bag until the pitcher is empty. Then I squeeze the bag again to get even more wort out. Generally, this top-off wort has a gravity in the low 1.020s. This all gets dumped into the kettle and stirred; I take and record another volume and gravity reading.

Boiling

Having recorded all of my pre-boil volume and gravity readings, I apply heat to the kettle and go. Once I’ve got a vigorous enough boil, I start my timer and follow along with the formulation as it’s printed.

My immersion wort chiller goes into the boil when there is about 30 minutes left on the clock. That is more than sufficient time for it to be sanitized.

I add 1 tablet of Whirlfloc with 15 minutes remaining in the boil.

I add yeast nutrient at a rate of ½ teaspoons per gallon with about 10 minutes remaining in the boil.

Chilling

The wort is chilled immediately after the heat is turned off. The wort chiller is hooked up to the faucet and the cold water is turned on full blast. I stir the wort to keep it circulating in the kettle; this helps speed up the cooling process. It typically takes me 15-20 minutes to chill 5.5 gallons of wort to between 70-80ºF.

Whirlpools and Hop Stands

If the formulation calls for whirlpool additions or hop stands, I will chill the wort first to approximately 150ºF; this preserves more of the volatiles and minimizes isomerization. If the formulation calls for whirlpooling, I will gently stir the wort with a stainless steel spoon or the mash paddle.

Post-Boil Science

Although I have taken notes throughout the brewing process, these are the most critical. I stir the wort to reduce stratification, run off a little bit through the kettle’s valve (just enough to fill a sample tube), and take a hydrometer reading. This is my original gravity. As long as I’m within about 2 points of my target, I’ll call it a success. I’ll also note the volume in the kettle.

Top-Off and Transferring Wort

I typically ferment in a 7 gallon stainless steel Brew Bucket from Ss Brewtech. This has been one of my best brewing investments. The stainless steel is much lighter than glass (though not as light as PET carboys), infinitely easier to clean than a carboy, infinitely safer than glass, and has a convenient sampling port. It may not be as nice as a fancy conical, but after I fermented my first beer in one, I wondered how I’d ever lived without one.

I attach a short length of silicone tubing to the valve on my kettle and run off the wort into the Brew Bucket.

After I finish transferring the wort, I shake the Brew Bucket for about 60 seconds to aerate. This helps to get a little more oxygen into the wort to assist the yeast during the early part of fermentation.

Pitching Yeast

After all the volume and gravity numbers are recorded, and the wort has been aerated, it is time to pitch the yeast. First, I ensure that surfaces are sanitary. Second, if I’m pitching from a starter, I double check that I’ve removed the stir bar from the flask. Then I double check that I’ve reached proper pitching temperatures; while this varies from strain to strain, I generally pitch at 64ºF for ales and at 50ºF for lagers.

Once I’ve checked all of the above, it’s time to pour in the yeast, cap the fermentor, and move it somewhere out of the way.

Fermentation

I have a chest freezer that I use as a fermentation chamber. The freezer is hooked up to an Inkbird ITC-308S temperature controller with a 12 inch probe; a fermentation heater is also plugged into the temperature controller, and held to the carboy with a bungee cord.

After pitching the yeast, I set the controller to the target fermentation temperature for that strain and style. For most strains, I set the controller on the lower end of the preferred range as indicated by the lab — usually about 2-4ºF above the lower bound. For styles where I want more ester production (e.g., saison) then I will go higher.

After setting the target temperature, I set the margins. I’ve had the best results with a ±1ºF margin around the set point.

For the first week after pitching, I attach a blow-off tube to the airlock and place the other end into a small bucket filled with a Star San solution. If the bucket gets a lot of krausen blow-off, I will swap it out for another bucket with fresh Star San solution.

During fermentation, I typically take observations about twice each day. I record the temperature as reported by the controller. I also record the number of bubbles per minute that appear in the airlock or blow-off bucket.

When the airlock activity has significantly slowed down (e.g., fewer than 6 bubbles per minute), I change out the blow-off bucket for a three-piece airlock. This is also about the time that I would consider raising the temperature by 1ºF per day until I get to 3-4ºF above the starting set point.

About 5-7 days after pitching is when I take my first gravity reading. I fill a shallow ramekin with the fermenting wort, pulling the sample from the Brew Bucket’s sampling port. And though I don’t 100% trust the refractometer, I’ll use that to get a ballpark on the current gravity. If the reading is stable over consecutive readings that are 2-3 days apart, then I consider the fermentation to be completed.

Dealing with Stalled Fermentations

I consider a fermentation to be stalled if the gravity stops dropping and it’s more than 3-4 points above the target final gravity. If this happens, I will add yeast energizer at a rate of ½ teaspoons per gallon. In addition to adding the yeast energizer, I would also raise the temperature 3-4ºF if I haven’t done so already.

If the yeast energizer and raised temperature do not help, I add a dose of rehydrated neutral champagne yeast — something like Lalvin EC-1118 or Red Star Premier Cuvée. (But if I’m adding one of these strains, that means harvesting is off the table.)

All that being said, these are hopeful methods that I’ve never actually observed to make a significant difference in the final gravity.

Racking to Secondary for Conditioning

When I first started brewing, I would rack from primary to secondary almost religiously. These days it’s only for the higher gravity or more complex beers (e.g., big stouts, American strong ales) that benefit from bulk conditioning. Perhaps it goes without saying, but a lager beer will get racked off its lees and into a keg before it’s cold conditioned.

When I do condition a beer in a secondary vessel, I wait for the primary fermentation to complete; in my experience this takes about two weeks. I open the port on the Brew Bucket and use gravity to drain into the secondary vessel. Once in secondary, most beers are conditioned for 2-4 weeks. Beers with strong or harsh flavors may be conditioned longer to let them mellow. Lagers are cold conditioned one week for every 10 points of original gravity.

Dry Hopping and Flavor Additions

I dry hop using a pair of fine mesh stainless steel cylinders. The cylinders are sanitized with a Star San soak. I’ll place up to 4 oz. of hop pellets in each cylinder which allows room for them to expand as they soak up liquid. The cylinders are placed directly into the Brew Bucket. Dry hops rest for 3-5 days before I remove them. After dry hopping, I will cold crash the beer and package as soon as possible.

Generally speaking, I dry hop at the following rates.

| Light | Medium | High | GTFO |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4-0.6 oz./gal. | 0.6-1.0 oz./gal. | 1.0-1.6 oz./gal. | >1.6 oz./gal. |

Fruit and Spices

I use a similar technique for adding fruit and spices during the conditioning period. I sanitize the mesh cylinders, place the fruit or spices into them, and place that into the beer.

For ingredients like peppers or vanilla, I will soak them in a neutral spirit (e.g., vodka) for 15-20 minutes before adding them to the conditioning vessel. If the amount of spirit is small (e.g., less than 1 pint) I will add that as well.

With fruit, I chop them into small pieces in order to maximize the surface area that will make contact with the beer. After chopping up the fruit, I freeze it for 24 hours to break down the cell walls to increase the flavor that will be released. After freezing, I thaw the fruit so that it does not shock the yeast when added to the fermentor. Once the fruit is thawed, I add it to the fermentor as soon as possible. If I want to be extra cautious 3 then I will soak the fruit in a neutral spirit for 15-20 minutes before adding it. 4

I haven’t worked with fruit enough to have a “standard” way of dealing with it. I also believe that the preparation and handling methods depend on the choice of fruit and the style of beer. Sanitation concerns are still present when dealing with fruit, and a vodka soak should take care of that, but I wonder how much flavor leaches out that way. I need to do more research in this area.

Packaging

I keg most of the time, and mostly bottle for competition using a Blichmann BeerGun. Bottle conditioning is mostly reserved these days when it’s “necessary” for the style (e.g., Trappist-style ales).

Bottling

The first thing that I do is to estimate how much beer I have. For a 5 gallon batch, on average, 4.2 gallons (roughly 44 × 12 oz.) make it into bottles. With this estimate, I use BeerSmith to calculate the amount of priming sugar I need; most of the time I use white corn sugar as the priming agent, though I have experimented with honey and maple syrup as well. Priming agents get mixed with 1 pint of water and boiled for 15 minutes. Priming solutions are cooled and added to the bottling bucket. Using an auto-siphon, I’ll rack the beer into the bottling bucket; the filling action is sufficient to mix the priming solution. I elevate the bottling bucket as much as I can before opening its valve. I use a bottling wand, filling each bottle until it is just level with the rim; removing the wand from the bottle leaves the correct amount of headspace. Bottles are capped immediately. When all the beer has reasonably been run out of the bottling bucket, I box up the bottles and stick them somewhere warm (i.e., 65-70ºF). In my experience, bottle conditioning requires at 1-2 weeks for sufficient carbonation; that said, I’ve been disappointed every time I sample one earlier than 2 weeks.

Kegging

When kegging, I rack the beer into a cleaned and sanitized keg. Once the racking is complete, I connect the COâ‚‚ to the keg and turn it on for 30 seconds; then I shut off the gas and pull the pressure-relief valve to purge the headspace. I repeat this 2-3 times (30 seconds of gas, purge headspace). If I’m not able to put the keg on gas for carbonation immediately, then I will put it in the refrigerator to keep it cold.

Once I’m able to, I put the keg into the kegerator and connect it to the COâ‚‚. I apply the gas at 40 PSI; after 24-36 hours I shut off the gas and purge the headspace. I turn the gas back on at 12 PSI and perform a trial pour. If it’s OK then we’re ready to serve; otherwise I’ll stick it back on at 25 PSI for another 24 hours, repeating the sample process as necessary.

Cleaning

Saving the most boring bit for last: cleaning.

First and foremost, everything gets cleaned as soon as possible. The longer it sits, the harder it will be to clean the vessel. I start by rinsing surfaces and wiping them down with a soft cloth; if the vessel is stainless steel, I might also use a scouring pad. If there is still debris on the vessel’s surface, I will put ¼ cup of PBW into it and fill it up with hot water for a 25 minute soak. When the soak completes, everything gets another wipe-down with a soft cloth and a thorough rinsing. After rinsing, the equipment is sprayed with Star San and allowed to dry.

Parting Thoughts

If I have any other advice for brewers, it’s to take lots of notes. For each beer that I brew, I keep a little journal for it in Evernote. When the beer is ready to serve, I do a BJCP-style structured evaluation, and then I write it all up here on this blog. This has helped me keep track of what was successful and what needed improvement. In other words, writing about brewing has made me a better brewer.

As for this write-up of my process and technique, it represents where I am now (circa July 2020) as a brewer, after roughly six years of brewing. It has been useful for me to think it all through and jot it all down; hopefully it comes in handy for you as well.

Revisions

Revision #1 (September 9, 2017)

- Updates related to water. New link to water report. And that I’ve started dabbling in mineral additions.

- Updated starter method; added information about over-building.

- Updated mash-out to indicate that I usually don’t.

- Whirlpool hops at 150ºF (down from 170ºF).

- PET carboys, not glass.

- Set point ±1ºF (not ±2ºF).

- Refined statement about raising fermentation temperatures.

Revision #2 (December 9, 2017)

- Updated “short-short summary” to reflect my move to a full volume, all-grain BIAB method.

- Clarified/refined notes on sanitation.

- Updated notes about water chemistry and adjustments; added link to baseline CWD Bru’n Water sheet.

- Clarified notes about aroma hops.

- Clarified notes about local PQM malts.

- Added footnote about rehydrating dry yeast, and how the improved quality is an unsubstantiated claim.

- Corrected O.G. of yeast starters (from 1.040 to 1.038 after performing a calibration).

- Removed statements about cold crashing yeast starters and decanting supernatant.

- Added comments challenging conventional wisdom around viability of harvested yeast slurries.

- Updated brew day section to indicate mashing/boiling in a 10 gal. kettle.

- Added footnote about “vigorous enough” boiling on the stovetop.

- Clarified statements about dry hopping in carboys.

- Added notes about writing about brewing.

Revision #3 (June 14, 2018)

- Commented on brew house efficiency approaching 72% “for real this time”.

- Refined explanation of “the Strong Method”.

- Added link on “choice paralysis”.

- Refined explanation of light-as-possible DME for starters.

- Added note about using Fermcap to control boil-overs on starters.

- Added note about petite mutants risk with yeast harvesting.

- Dropped reference to being “single-vessel stove-top brewer”; that is less true now that I’m brewing in the garage more often than not.

- Dropped reference to pH 5.2 stabilizer.

- Updated brew day and wort transfer discussion to discuss using the ball valve on my kettle.

- Added note about not harvesting yeast if otherwise supplementing with a champagne yeast.

- Significantly curtailed discussion of conditioning in “secondary” carboys.

- Snarky remark about not having a good method for dealing with dry hops.

- Added dry hopping rate chart.

- Updated kegging procedures.

- Updated some images.

Revision #4 (December 22, 2018)

- Updated link to Champlain Water District report to refer to the current 2018 report.

- Added notes about carbon filtering the water.

- Updated Bru’n Water references to reflect usage of BeerSmith 3 for working on water profiles.

- Assumptions updated to reflect 70% brew house efficiency, as observed throughout the past year.

- Dropped rubric about “when to make a starter” for liquid yeast because I basically always make a starter.

- Added explanation of my mash out technique for BIAB.

- Updated fermentation sections to reflect that I mostly use a 7 gal. Ss Brewtech Brew Bucket as my preferred vessel.

- Generally tried to simplify language throughout the post.

Revision #5 (July 26, 2019)

- Updated statements about brewing water to reflect the move from Vermont to Seattle.

- Removed the statement about adding dark grains during the last 15 minutes of the mash; I’ve concluded that that’s more work than it’s worth.

- Added statement about how “dealing with stalled fermentation” is hopeful-at-best and I’ve never actually seen it work.

- Miscellaneous updates to “de-Vermont” the piece.

Revision #6 (January 1, 2020)

- More Seattle-specific updates, mostly with respect to water.

- Specifying 70% as brew house efficiency for moderate-gravity batches, vs. 65% for high-gravity batches; also linking to analysis.

- Fixed an unfortunate typo in the starter instructions.

- Removed the bits where I “challenge” the conventional wisdom about re-pitching “old” slurry.

- Removed the bit about using the pulley in the garage. R.I.P. pulley. R.I.P. garage.

- Miscellaneous clean-up.

Revision #7 (July 15, 2020)

- Added Warrior to my list of go-to bittering hops.

- Started using Whirlfloc instead of Irish moss; updated to reflect that.

- Some miscellaneous photo updates.

- I use the lightest DME I can find; Briess Pilsen or Golden Light DME are both fine.[↩]

- The Reflectix works pretty well. I wrote an article about it for BYO: “Insulation for Single Vessel Brewing” — which is currently paywalled, but there you go.[↩]

- …less adventurous?[↩]

- And then hey now we’ve got vodka with a strawberry infusion?[↩]

Leave a Reply