BJCP Study Group: Categories 3 & 14

¶ by Rob FrieselStudy session #14 was originally going to be dedicated solely to Category 14 (Scottish Ale), but a couple of factors came into play that allowed us to double up. First, other than a couple examples of 14C. Scottish Export, our coordinator for the night was having a real bear of a time finding any beers to demonstrate the other styles. In a bit of a windfall though, we discovered that we had enough examples of Category 3 (Czech Lager) that we could mix in that one to make the best use of the evening’s session.

Categories 3 (Czech Lager) & 14 (Scottish Ale)

As I mentioned above, these two categories were brought together more out of convenience than out of any kind of thematic similarity.

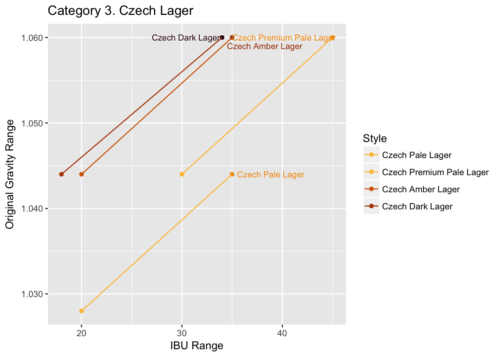

Though we were missing an example for 3C. Czech Amber Lager, we (to our surprise) managed to cover the other three styles within Category 3. The examples we had included a couple of Czech imports (cans, brown bottles, and green bottles), a homebrew example, and a locally brewed interpretation. Unlike Category 14, whose styles are differentiated along gravity lines, the Czech Lager styles are largely differentiated based on their color. That being said, the guidelines for 3A. Czech Pale Lager seem to tilt it toward the vyÌcÌŒepniÌ class as a way of making room for low-gravity interpretations of the Czech styles; meanwhile the other three styles appear to cover the lezÌŒaÌk and speciaÌlniÌ classes in the Czech tradition. All of the styles within the Category could be described as “rich and bready” malt-forward beers with spicy or floral or botanical hop bouquets. As the styles get darker, you should see more Maillard products, sweeter and more biscuity flavors, more caramel notes, with 3D. Czech Dark Lager even including descriptors like “nutty”, “dark fruit”, or “cola”. Once again, as with other dark European styles: “toast, not roast”.

| 3A. Czech Pale Lager | 3B. Czech Premium Pale Lager | 3C. Czech Amber Lager | 3d. Czech Dark Lager |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 – 35 IBU | 30 – 45 IBU | 20 – 35 IBU | 18 – 34 IBU |

| 1.028 – 1.044 O.G. | 1.044 – 1.060 O.G. | 1.044 – 1.060 O.G. | 1.044 – 1.060 O.G. |

| 1.008 – 1.014 F.G. | 1.013 – 1.017 F.G. | 1.013 – 1.017 F.G. | 1.013 – 1.017 F.G. |

| 3.0 – 4.1% ABV | 4.2 – 5.8% ABV | 4.4 – 5.8% ABV | 4.4 – 5.8% ABV |

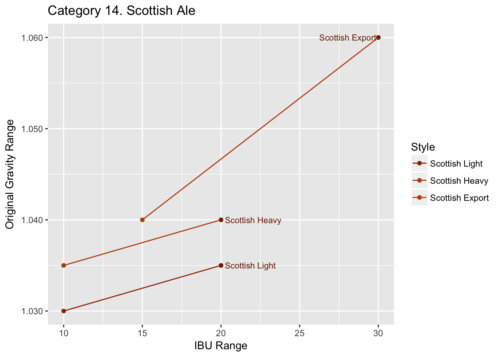

Though we were only able to find two examples of one style for Category 14, we felt that we would need to make due with what we had — after all, the three styles differed almost entirely on the basis of original gravity. It would have been nice to compare two styles within the category to get an idea of how those differing strengths would be perceived back-to-back. (But alas!) For what it’s worth, we called out that all three styles within Category 14 had nearly identical descriptions. Scottish Light (14A) is mostly commonly the darkest. Scottish Export (14C) can tolerate more bitterness. All of them are entirely malt-focused (toasted breadcrumbs, lady fingers, English biscuits), with roasted accents (but never “roasty”); any bitterness should be there to balance, and any yeast character should be consistent with a British heritage. Oh, and peat smoke is never appropriate.

| 14A. Scottish Light | 14B. Scottish Heavy | 14C. Scottish Export |

|---|---|---|

| 10 – 20 IBU | 10 – 20 IBU | 15 – 30 IBU |

| 1.030 – 1.035 O.G. | 1.035 – 1.040 O.G. | 1.040 – 1.060 O.G. |

| 1.010 – 1.013 F.G. | 1.010 – 1.015 F.G. | 1.010 – 1.016 F.G. |

| 2.5 – 3.2% ABV | 3.2 – 3.9% ABV | 3.9 – 6.0% ABV |

- 14C. Scottish Export. Belhaven Scottish Ale. Judged; structured tasting. Turns out these were “nitro” cans with a little Guinness-esque widget inside. The addition of nitro certainly enhanced any creaminess that we would perceive, but this reduced the impression of carbonation (expected) as well as reducing the impression of body (unexpected). Even for a style which can have low carbonation and “medium-low” body, this seemed almost too thin to several of our aspiring judges. Several also remarked on a distracting hint of metallic or “tinny” quality, especially on the palate. Most scored this in the 36-38 range, with only one issuing a 31.

- 14C. Scottish Export. Drop-In Heart of Lothian. Not judged, no structured tasting; mostly as a comparison to the previous example. This was a beer that most (all?) of us at the table were familiar with. Being a locally-brewed interpretation of the style, it was interesting to compare it to the imported Scottish ale that we’d just scored. For starters, this beer was carbonated with CO? (not nitro). Our coordinator for the night had brought along a sell sheet for this beer from the brewer, and so we talked through the ingredients, trying to figure out roughly what proportions would result in a beer with this character. As with many American interpretations of these traditional beers, it seemed to pack a little more punch (vis-à-vis gravity and ABV), though we also agreed that it seemed to still fit comfortably within the Category.

- Aside: Scottish Ale vs. Dark Mild? Though we did not have examples of 14A and 14B to drink, someone did point out that that 14A. Scottish Light seemed to have a very similar profile to 13A. Dark Mild. We walked through the guidelines for each and… had a real hard time drawing a clear distinction. I don’t believe that we came to any kind of firm conclusion.

- 3B. Czech Premium Pale Lager. Pilsner Urquell. Judged; structured evaluation. The classic example of the Czech lager? At least the one that seems easiest to get in the United States. For the judged round, we poured from bottles; our scores were largely clustered in the mid-to-high-30s. Most of us acknowledged that all the expected aromas and flavors were present, but that they seemed duller or less intense than we’d expect for something “Premium”. Perhaps it was old and oxidized? We did a second round “quick comparison” with some fresher cans of Pilsner Urquell. These were brighter and clearer; no skunky off-aromas (though not all of us picked up on that on the first go-around), and the bitterness was better pronounced.

- 3B. Czech Premium Pale Lager. Czechvar B:ORIGINAL. Not judged. As one of the group joked: “Obviously the gold foil top keeps it fresher.” Green bottles. Obviously lightstruck — unlike the Pilsner Urquell, everyone perceived the skunky quality here.

- 3A. Czech Pale Lager. Homebrew example. Not judged, though we should have. This was a beer with numerous faults. It was soapy-tasting and sour. (“Palmolive?”) And though we didn’t fill out a scoresheet for this one, we did talk through what kind of feedback we would have given, and how we could phrase that feedback such that it would be constructive. For example, if commenting on the sour character, inquire about the yeast strain and the fermentation conditions, and also suggest that the brewer check on their sanitation regimen.

- 3B. Czech Premium Pale Lager. Primátor Premium. Not judged; no scoresheet. But also my notebook doesn’t have any notes here. We must have rushed through it on our way to…

- 3D. Czech Dark Lager. Zero Gravity Bohemian Dark. Not judged, but thoroughly discussed. It was on the lighter side of style’s color range (enough so that some joked that maybe it was a 3C?) but in every other way seemed to be a solid example of the style. Several group members remarked on the “cola” quality coming through on the aroma and palate, with rich and multi-layered perceptions throughout.

- Bonus beers. One of our group had brought in a recent lager beer experiment; this led to a discussion of what sort of faults might occur from under-pitching (which was the working hypothesis for this beer’s flaws). Meanwhile, to finish up the night, there was some kind of side-by-side comparison happening — but I’ll admit that I’d gotten distracted by a sidebar conversation and didn’t really know what that was about.

Takeaways

The themes and broad observations from the night:

- Watch out for nitro cans. If you’re training with commercial examples, watch out for those little nitro widget cans. They may be pleasing to drink, but they’re not necessarily going to give you a close enough facsimile to what you’re likely to judge in competition.

- American interpretations of traditional styles. I feel like our group has encountered this a couple of times now. When you have an American brewery making an interpretation of what’s otherwise a traditional European style (British or Continental), they tend to be on the stronger end of the style’s range, or even a little over. While this makes sense (i.e., to appeal to the domestic market), it won’t necessarily give an accurate picture of the style for competition purposes. They’re usually close enough, so they’re better than skipping a style all together, but it’s worth taking that into consideration while training.

- If you have homebrew examples, score them. Our group has made this mistake a couple times. In the rush to judge a palate-pleasing, high-quality example — something that you expect to give you a glimpse into what the style should be — it becomes easy to lose sight of the fact that they may not represent the kind of beers you’ll score in competition. It’s equally valuable (perhaps even more valuable) to get experience scoring flawed beers and providing constructive feedback.

- Sidebar discussions and distractions. I feel like we’re usually pretty disciplined and focused, but for whatever reason, it was too easy to get off the subject and onto sidebar discussions. Maybe it had just been a long week for everyone? I don’t know, but I let myself fall victim to this one and suspect I may have missed out on something toward the end.

About Rob Friesel

Software engineer by day. Science fiction writer by night. Weekend homebrewer, beer educator at Black Flannel, and Certified Cicerone. Author of The PhantomJS Cookbook and a short story in Please Do Not Remove. View all posts by Rob Friesel →3 Responses to BJCP Study Group: Categories 3 & 14

Pingback: Homebrew #81: Half Dark | found drama

Leave a Reply