BJCP Study Group: Category 17

¶ by Rob FrieselCategory 17 was the occasion for our 18th BJCP study group session. Only six categories left to study — over 75% of the way through our rubric. A fun category with some interesting variety despite the common thread running through them.

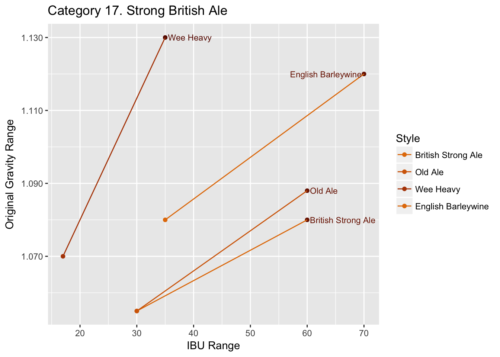

Category 17. Strong British Ale

The BJCP style guide’s summary for this category is so pithy it doesn’t even warrant a blockquote, just: This category contains the stronger, non-roasty beers of the British Isles.

| 17A. British Strong Ale | 17B. Old Ale | 17C. Wee Heavy | 17D. English Barleywine |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 – 60 IBU | 30 – 60 IBU | 17 – 35 IBU | 35 – 70 IBU |

| 1.055 – 1.080 O.G. | 1.055 – 1.088 O.G. | 1.070 – 1.130 O.G. | 1.070 – 1.120 O.G. |

| 1.015 – 1.022 F.G. | 1.015 – 1.022 F.G. | 1.018 – 1.040 F.G. | 1.018 – 1.030 F.G. |

| 5.5 – 8.0% ABV | 5.5 – 9.0% ABV | 6.5 – 10.0% ABV | 8.0 – 12.0% ABV |

The unifying elements for these four styles are an overall impression that is defined by deep/rich and pronounced malt, a chewy body, and some British-heritage yeast character, particularly with respect to fruity esters. All four style descriptions make reference to alcohol warming that is “smooth” and “evident”. What’s most interesting is studying what makes these four styles different. Hops, for example, play little to no role in the aroma/flavor profiles for Wee Heavy and Old Ale; meanwhile a variety of hop-derived sensory impressions and intensities are acceptable for British Strong Ale and English Barleywine. An Old Ale can take on a vinous character, almost like Sherry or Port. Wee Heavy feature significant caramel, as opposed to nutty, toffee, bready, or biscuity. Lastly the main thing to differentiate British Strong Ale from English Barleywine appears to be the level of richness and intensity.

With no new members joining us tonight, and no BJCP mentor to lecture us, we dove into the styles.

- 17A. British Strong Ale. Samuel Smith’s Winter Welcome Ale. Judged; structured tasting. A larger spread than I think we’d usually have, especially early in the night; we ranged from the low to high 30s, with maybe a couple scores in the low 40s. Those of us at the table had a range of opinions, many of them in conflict. We’ve run into these kinds of discussions before, especially with styles that have “a wide range of interpretations” like this one. It can be difficult sometimes to agree whether something like “low-level of diacetyl” in the aroma is at an appropriate level to be acceptable, or an indication of a major flaw. One thing we all seemed to agree on was the presence of a tinny metallic note; some thought that this contributed to the impression of astringency in the mouthfeel that distracted from what might have otherwise been a smooth ale. It also raised some interesting questions about how to deal with sensory impressions that may be derived from water chemistry, and are seldom discussed in the style guidelines.

- 17C. Wee Heavy. Orkney Brewery Skull Splitter. Judged; structured evaluation. Much tighter cluster of scores this time around; almost all of us within 2 points on either side of 40. Very favorable impressions of this beer. We did an inventory of the sensory impressions that people got, and with much agreement and overlap: strong caramel, moderate toffee, medium grainy-sweet, no significant hop impressions, esters like raisin or dried cherry, full body with moderate (but noticeable) alcohol warming. Where we quibbled was over mouthfeel: was the body right on, or did it need a little more weight? was the carbonation too low, or right on? Nevertheless, consensus was that we had a well-balanced and rich Wee Heavy.

- 17C. Wee Heavy. Homebrew example. Not judged; no structured evaluation. Impressions only, and mostly to compare with the Skull Splitter. We went around the table for some spit-ball first impression scores: mid-20s to low-30s. “Why there?” was the challenge statement — what was the major contributor to that off-the-cuff score? For the most part, the explanations centered around the fact that this homebrewed example lacked the richness and complexity of the Skull Splitter. It was a one-note beer, and that one note was “too much caramel sweetness” and possibly under-attenuation.

- 17B. Old Ale. North Coast Old Stock Ale. Not judged; no structured evaluation. The general impression at the table was that this example was “too hot” — in a solventy alcohol sort of way. While an alcohol impression is desirable in the style, it should be smooth. Here the alcohol just seemed to overwhelm any other sensations you might get. Was there a molasses or nutty impression in there to add complexity? Impossible to tell! We wondered if this was just a “too young” Old Ale that needed to go into the cellar for another year to mellow out.

- 17B. Old Ale. Homebrew example; two partially-filled bottles from the club president that had been capped less than 24 hours beforehand. Not judged; no structured evaluation. “If I recall correctly…” both of these were the last of Jason’s take from when Aaron brewed Rock, Stock, and Barrel at Vermont Pub and Brewery. (Though Aaron insisted that even if it were “something was different about this one”.) A lot of molasses character, and maybe a little minerally (though Aaron explained that if it was his, it was unsulphured molasses and so that wasn’t it). Pours were small, and we moved on quickly.

- 17D. English Barleywine. Homebrew example. Not judged; no structured evaluation. Many at the table got a strong “creamed corn” and/or “candy corn” impression from this one, and we suspected a DMS fault. (I personally didn’t get a “big” impression of it and wonder if there wasn’t some mob mentality happening there…?) Regardless of that (debatable) impression, it was also a little thin in the body and was lacking in complexity. Spitball score would have been in the high-20s.

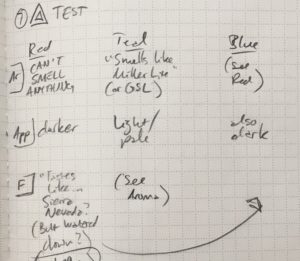

- Triangle Test. Our sensory exercise game is getting a little stronger and more consistent, mostly thanks to Erin. For this session’s exercise, it was pretty obvious which was the odd beer out (i.e., stark color difference) so the emphasis was on: Can you explain what makes them different? Looking over my own notes:

Red and blue cups? Can’t smell much of anything. Teal cup? “Smells like Miller Lite?” Red and blue cups? Obviously darker. Teal? A very light/pale color. What about the taste? Teal? “(See Aroma.)” Red and blue? “Tastes like… Sierra Nevada? But watered down?” And so what could the difference be? “Watered down” was as specific as I could get — that the body seemed too light (especially for the color) and… and what? So then Erin did the reveal for us:

- Bonus beers. A few homebrews went around. A one year old extract Irish Red Ale. Some homemade cider. A mulberry-smoked porter. A possibly under-attenuated Märzen.

Takeaways

- How to arrive at consensus when broad interpretations are allowed? I think we (as a group) continue to struggle with this one a bit. Justifying your own particular score is one thing, but convincing the other judges is another. And/or allowing yourself to be swayed a bit. Seems a good place to apply two axioms: (1) “Overall impression over individual sensations” and (2) “Strong opinions, weakly held”.

- Be wary of strong beers. Two things that came out of this, at least for me. First, we’ve learned to show some caution with strongly hoppy and bitter beers; the palate-wrecking qualities there are something we understand well. Strong alcohol impressions will do the same thing. Second, if the alcohol impression overwhelms the other sensory impressions — that’s bad.

- How to deal with minerally impressions and water chemistry? This is a topic our group still needs to explore in a little more depth. Is a “tinny” or “coppery” impression from the mineral content of the water? or something else? How can you infer the difference? If the style guidelines don’t discuss that specifically, what do you comment on? Do you default to “inappropriate”?

Leave a Reply