Farewell, Vermont

¶ by Rob FrieselOur original plan was never to stay. We came for Amy’s graduate school, with every expectation that we would be gone in four or five years so she could chase a post-doc and then a tenure-track role after that.

But that’s not how things shook out, and all the subsequent decisions — large and small — accreted into a 17 year stint that looked like it might keep us here for good.

But that’s not how things shook out either.

We moved here in 2002 so Amy could attend the University of Vermont for graduate school.

When her graduate advisor moved to Dartmouth in 2004, we decided our best move was to split the difference distance and take up residence in Barre until we could figure out what was next for us.

After she defended her PhD in 2006, we decided to stay in Vermont “for now” — in part because my career was doing well at Dealer.com and it seemed like, even if it wasn’t the best place to grow her science career, she could at least make a go of it. So we moved “back” to Burlington.

When Holden came along in 2008, it seemed like we just made Vermont our permanent home.

…just not on North Avenue. With H. in the mix, we moved out to Essex Junction to settle down. Found a place that felt like home, made some friends on the block, and started treating the place like we might be there a good long while.

Then Emery came along. And maybe we could have stayed in that house and been happy and made it work, but some happy circumstances aligned and we moved all of about a mile into a house on a cul de sac that for real this time we even said out loud: “This is it. We’re not moving again until the boys are grown.”

But that version of the story leaves out a lot.

That version of the story leaves out how Amy lost her research gig shortly after Holden was born. It leaves out how she chased research and academic work for another few years. And how those roles paid poorly and always had tenuous futures.

That version of the story leaves out how she courageously walked away from science and from her PhD, because it wasn’t going anywhere, and the sacrifices needed felt too much like gambles instead of investments. It leaves out the struggle of reinventing herself — of looking for a new career where she could take her foundational skills and apply them to something she loved doing and that people would pay for. It leaves out how she made her way from behavioral neuroscience into user experience research.

That version leaves out hours and hours of self-guided reading and volunteering and long-shot freelance consulting. It leaves out the triumph of landing her first salaried role. And it also leaves out the frustration she felt when, three years after landing that role, organizational changes made it… nearly impossible to do her best work.

If you don’t know her, the main thing that you need to know about Amy was probably best summarized by my friend Dave:

Amy is a feisty bad-ass who doesn’t respect disciplinary boundaries.

(Take a moment to pick that one apart in all of its highly appropriate interpretations.)

Anyway, as 2018 closed out, the time had come for her to make some changes. She left that job and tried some new things in the same wheelhouse where she’d found her recent success. UX consulting. Product development. Business strategy. And it wasn’t that these things weren’t working but… I think she and I could both tell that her talents were calling to her.

It might sound strange, but it shook out from a date night. We did the tasting menu at Single Pebble. We danced our asses off to Nightmares on Wax. We got back outside to the car and cursed the totally normal but totally stupid March snow that had accumulated. She looked serious. “What if,” she asked, “what I need to do isn’t here? What if we need to leave Vermont for me to do what I’m really good at?”

My memory of my reply in the moment is poor, but the sentiment would have been the same as the line I used dozens of times since then: “It’s not that I want to leave, but I’m willing to if that’s what it takes.”

I’ll skip over a lot of what comes next because it’s not really important.

What is important: we took a vacation to Seattle with the boys. If I recall the timeline correctly, we planned the trip before the Seattle-based recruiters got in touch with her, but they also got in touch with her after said trip was booked. So we approached that vacation (in part) as a scouting mission. Could we see ourselves there? Could we see the boys there? What trade-offs would we be making by going there and leaving Vermont? Would those trade-offs feel like a net gain? a net loss? break even?

And if you’re reading this post, I suppose it goes without saying, but it at least felt like a “break even” to us. Because a few weeks after our trip, she did back-to-back trips back to Seattle for interviews.

And when the offers came, there was only one thing I could say: “Babe, I’m super proud of you and this is a big deal and I’m behind you 100%.”

It’s not that I want to leave, but I’m willing to if that’s what it takes.

I joke at work sometimes about the clarity between our desire to do a thing and our willingness to do a thing. There have been all kinds of shitty tasks over the last 16 years that I have had zero desire to do but I did them anyway because they needed to be done and I understood why and I was the right person at the right (or wrong) time.

This isn’t exactly like that.

Like I said, our original plan for Vermont never included staying. But there sure is something magical about this place that makes you want to stay.

So yes, it’s absolutely difficult to say goodbye.

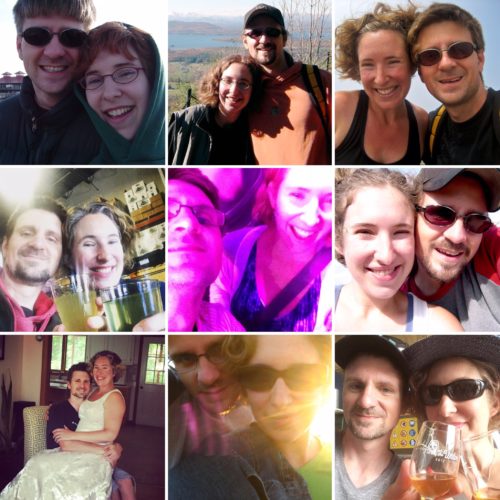

I got my first “real” job here. This is where we adopted Buca and Stoli (and Gracie). Holden was born here, and so was Emery. We drank some amazing beer. I learned to homebrew here and won my first award and met Gordon Strong who inspired me to learn to judge. I got involved in a homebrew club and learned how to make friends that weren’t work friends. I became three-time Vermont Mead Maker of the Year. I published my first articles. I wrote and published my first book. I skied a lot and then some more. Holden learned to ski, and so did Emery. We sledded and built snowmen and got snowed in and ice climbed and got into snowball fights and sledded some more. We witnessed those intense Lake Champlain sunsets. We learned to garden. We toured granite quarries. We hiked and hiked and hiked and hiked and hiked. We did Free Cone Day at the source! We learned about how obscenely inefficient maple syrup is. We got into apple picking and cider donut eating. We made local investments that expanded and paid off. Emery and I had our Tuesday thing for a while. Holden fell in love with the trumpet. I taught a lot of people how to make mead. I played cards with Batman. I watched two friends go head-to-head rather intensely. We tried to help out in the community. And while we were at it, we made a lot of friends — maybe more friends than we can reasonably count.

And looking at that paragraph, I’m reminded again of how hard the decision was. And all the people and things we’ll be leaving behind. There is plenty of sorrow, but no regret. We did more here than we ever imagined we would. Our experiences ran deeper, our friendships stronger, and our lessons longer-lasting. We wouldn’t trade a second of our Vermont experience for anything. And in many ways, this place has felt more like home to us than anywhere else we’ve ever lived.

And we say that even considering that our original plan was never to stay.

About Rob Friesel

Software engineer by day. Science fiction writer by night. Weekend homebrewer, beer educator at Black Flannel, and Certified Cicerone. Author of The PhantomJS Cookbook and a short story in Please Do Not Remove. View all posts by Rob Friesel →3 Responses to Farewell, Vermont

Pingback: Homebrew #90: Ned | found drama

Pingback: the long drive home | found drama

Leave a Reply